Key points:

- What does it mean to know a word?

- Getting started

- Choosing words to teach

- Creating the student resource

- Decoding the list of vocabulary words

- Next steps

When I asked my students what they felt was their biggest need, many of them responded with a version of the statement I’ve used as the title for this blog post – “I don’t have enough words.” As a second language teacher, I’ve been aware of student frustration around the challenges of learning a language for a long time. This statement gets to the heart of what we are learning through the science of reading. In order for students to build reading comprehension, they have to know words.

What does it mean to know a word?

Knowing words is a complex idea by itself – in her interview on season 8, episode 7 of “Science of Reading: The Podcast”, Dr. Tanya S. Wright explains what it means to know a word. She explains that we need a lot of information about a word and that a dictionary definition is not enough, especially for readers who don’t have enough vocabulary to understand other words used in a definition. She explains a more “informal” idea of a definition, which may include synonyms or antonyms, what “category” a word may belong in (grouping it with other words representing similar ideas or characteristics), multiple meanings of words that may occur in different contexts, disciplines, and idioms. We also need to know things like spelling, pronunciation, word parts and word families, any changes that may take place in a word depending on context, and other characteristics and syntax rules that apply to that word.

Traditional approaches to language instruction tend to rely heavily on translation-based models, which can cause many problems when we want students to make the jump from what we hope is a simple translation to using a word in oral or written communication or understanding it in reading, listening or viewing. We assume that because languages are similar and cognates signal a strong relationship, students will automatically transfer knowledge and meaning from one to the other. While this is sometimes the case, there are gaps that can lead to confusion, frustration and misunderstanding. Cognates can be a very helpful place to begin learning, but actual word knowledge is a much bigger picture.

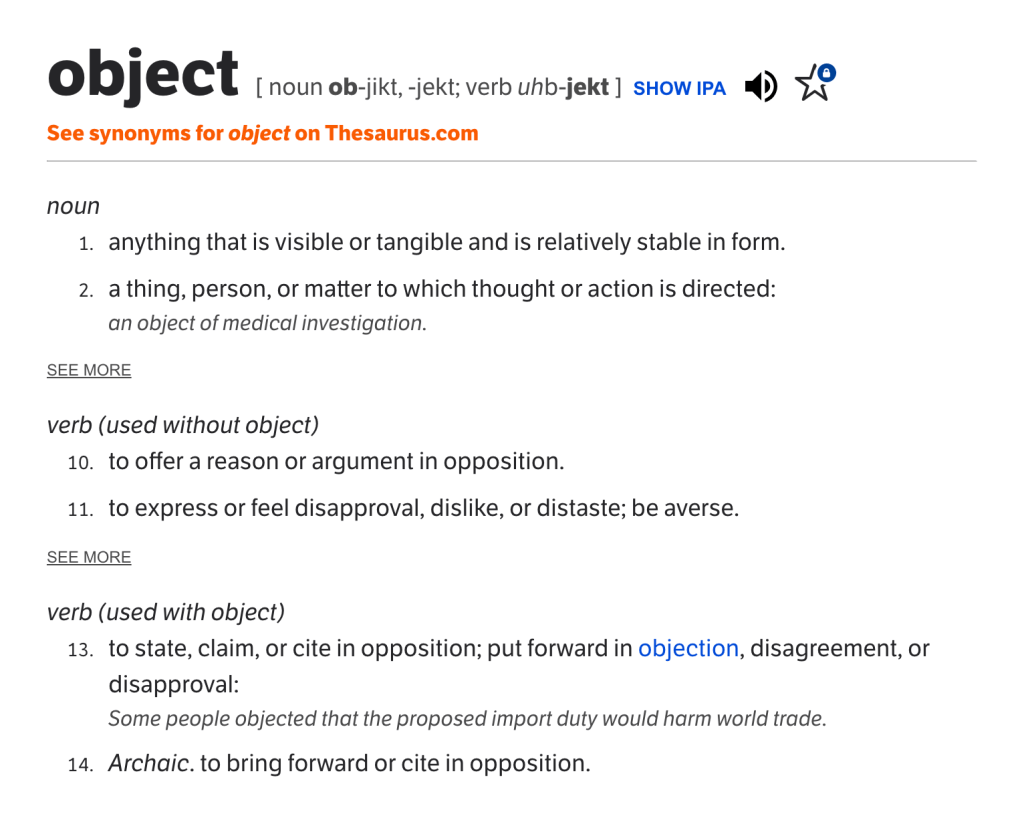

For example, in a unit I’m currently working on, students encounter the word “objet” (equivalent to our English word “object”). The Larousse online dictionary definition of this word gives 15 different possible meanings for this word. Knowing that my students will be working from English to French (at least in their minds), I also consulted an English source to see if there were any connections I might have overlooked. Dictionary.com lists 14 possible meanings. We’re one word in, and we already have a lot of complexity and possible mismatches between English and French. Digging a little deeper, we see that all 15 of the Larousse definitions of this word in French relate to its use as a noun. The Dictionary.com definitions relate to its use as a noun, as a verb used with an object, and as a verb used without an object. The OED brings even more complexity to the table by also listing ways in which “object” can be used as an adjective.

Getting started

I started by thinking about my audience. They are in French 10 but don’t yet have a wide range of word knowledge. I wanted to keep things simple and set them up for success in this first unit of the course, so I chose one meaning. It’s directly connected to the content of the unit (focused on identity) and the ways in which they will be asked to use the word in the unit. I’m defining it for now as a concrete thing that has a certain use. Throughout the unit, they will be asked to do tasks such as list objects that relate to interests they have, identify other people’s interests based on objects they have, generate ideas for objects and tasks a person with a certain interest might use, and so on. I’ve let them know that there are other possible meanings and that they will encounter more in the future, but starting here allows an access point for all the learners in my group.

Choosing words to teach

The unit I’m working with has a vocabulary list that the original designers put together. It contains a lot of useful words, but there are 87 of them. That’s a lot, and if I were to take a traditional approach, the sheer volume of information would demand so much focus on memorizing the words that there would be little time left over for developing reading, writing, speaking and listening. Some of the terms are very specific and have only one possible use, and others are more general and have a wider range of applications. There’s a mixture of nouns, verbs, adverbs, adjectives, and expressions that can be used in certain situations.

One of the ways in which I hope to help the learners in my classes acquire more words is to focus on a more limited set of words that they can use more widely. I started with the words themselves and a simple definition of each that I adapted from dictionaries intended for children. Where more than one definition was possible, I limited my options to just those that are pertinent to this unit. I’ve narrowed down that list of 87 to just 8. I chose them carefully, making sure that the ones I selected are Tier Two words – that is, words that are high frequency within the language my students will be exposed to in this unit but not so specific that they have very domain-specific uses (Tier Three) or so common that they will be used in basic contexts that don’t require instruction. The words on this list can also be used as subheadings for a word map that students will build to create a portrait of their own identity. As Tanya Wright says, vocabulary is unconstrained. There is literally no limit to the number of words that we can learn.

Creating the student resource

I thought carefully about how to introduce my students to the words we would work with. I knew that if I gave them a short list of only 8 words with no other information attached, the list would not seem important and could easily get lost in the other things we worked on in class. I needed my students to engage with the words and to think about them in ways they might not have thought about vocabulary previously.

Using ideas adapted from a Landmark Outreach workshop presented last year by Deirdre Mulligan, I began by creating an A-Z sheet of my 8 words. Organizing them alphabetically mimics the way that students need to search for information in a dictionary, another skill area I’m always looking to build up. For each word, I listed the first letter of each word followed by a blank that students would fill in once they figured out what the missing word was, the number of syllables in that word, and a simple definition of the word in French. In each definition, I highlighted the first word to draw students’ attention to it. This helps them to determine what part of speech the word they need will be. If the definition begins with a noun, they need to find a noun. If it begins with a verb, they need to find a verb. For this unit, I am using either nouns or verbs. In her workshop, Deirdre Mulligan recommended using tier 3 words to make the list, but because I’m working with learners who are trying to acquire language, I wanted to make the words more accessible and applicable to everyday communication.

Explicitly including the sounds of words

My second language students are used to using dictionaries or translators to figure out what words mean, what words to use in a piece of writing, etc. In order to decode these words, I wanted them to think about words in a different way, using the sounds of words. This was something they could not look up in any of the usual places, and they had to figure it out as a team. Keeping the list short made this a doable task, and working in groups of 4 gave them the opportunity to make suggestions and work together. Languages have their own ways of dividing syllables, and you can find a good summary of the rules for French syllable division here. Most of my students have already worked with syllables and sounds of words in elementary school, and they have learned to clap or tap while saying a word to separate the sounds and incorporate movement. Kinesthetic learning tends to form stronger connections in our memories, something I hoped would make these words stick.

Decoding the list of vocabulary words

Listing the words this way means that students have to figure out what the words are by engaging with their spelling, sound (represented by the number of syllables), part of speech (using the highlighted words) and meaning. Working collaboratively in groups of 4, students began by looking at words that looked like English (cognates) and words they already knew from their background knowledge and only using their French-English dictionaries to look up words they didn’t know yet. They highlight those first two categories using two colours of their choice (one for cognates, one for words they know) and then write in the meanings of the words that are new to them.

The engagement I had been hoping for started right away. As they worked on figuring out the words, I noticed them talking to their groups about what they knew and what they didn’t, writing down their guesses, going back to figure out what they might have missed when something didn’t make sense, and saying the words out loud to try to figure out how many syllables each word contained. Using a kinesthetic learning strategy many had learned in elementary school, many students clapped, tapped, and bobbed their heads as they said the words. If they weren’t sure how to say the words, they used the How to Pronounce app (iOS only) or Forvo.com to learn how to say the words. Because they were working in groups, they said the words to each other and checked their understanding by saying them to me, and I instantly saw more practice than I could ever get with a more traditional approach. The paper students were working on was covered with notes and has become an ongoing reference tool for them as we work through the unit.

When each group had guesses for all the words on the list, we reviewed the answers together. We talked about how they figured it out, what they had looked at that helped them find the correct answer, what each word sounded like, and so on.

I always ask my students to write down what they need in order to support their own learning. If they aren’t sure how to say a word, I show them how to write it phonetically and create a reminder they can go back to and practice from. If they don’t know what something means, I ask them to write down just that one piece. Writing in the meaning of a word they already know doesn’t help them to know it more, but it can make it harder to find that one thing they might be looking for when they review. They learn to trust that their brain will fill in the meaning of what they already know, and the support they need for new words is more easily accessible. As a teacher, I won’t always know what a student thinks of when they look at a word. If they develop a sense of agency over what to write down, my hope is that they will begin to feel more of a sense of control over the learning, and less of a sense that vocabulary is happening TO them.

Next steps

Taking time to do this in class is a big investment, and I wanted that time to pay off for me as a teacher and for my students as learners. In planning my unit, I wanted to create as many opportunities as possible for students to return to this core vocabulary list, make new connections to the words on the list, and use the words in their own communication. In my next post, I’ll explain more about how we’re using these words.

Photo by Debby Hudson on Unsplash