Key points:

- Connecting vocabulary to reading comprehension

- The basic foundation

- Practicing with the basic foundation

- Expanding the foundation

- Considerations around word substitution

- Why synonyms and antonyms?

- Connecting vocabulary to skills

- References

In my practice as a second language teacher, I have shifted to a short core list of vocabulary words for each of my units of instruction. This list has become a kind of axis around which many other parts of a unit are constructed. Language teaching and learning often centers around skills and strategies, and I teach these throughout the semester. However, in order for students to have repeated practice with skills and strategies and NOT see them as linked only to one content area, the content has to change.

Connecting vocabulary to reading comprehension

Paris (2005) refers to vocabulary as an “unconstrained skill” and one that we continue to develop throughout our lives. The number of words that are possible to learn is limitless, but language instruction has often been approached with very limited sets of words that were learned through rote memorization. Learning vocabulary from lists was a longstanding feature of the grammar-translation method of language learning. Those lists were often used to feature certain features of spelling and/or grammar, and were typically organized according to parts of speech as well as thematic organizers. The lists were usually fairly long, and student knowledge of the words was assessed using quizzes or tests that were translation-based, mapping the second language words to first language words.

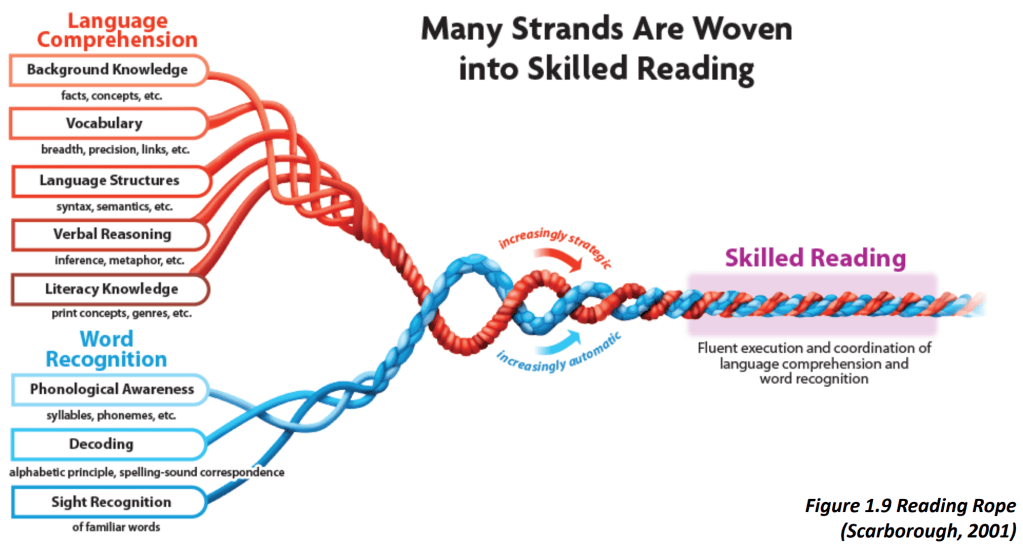

My goal is for my students to build second language vocabulary knowledge that is more interrelated. I want them to know the sounds, the spelling, possible variations (singular, plural, masculine and feminine forms, and conjugations), the syntax connected to the words, as well as the meaning. I also want the words to be a little more connected to imaginative and literary text. I want to increase the complexity of what students can say and do with the language they learn. These aspects of word knowledge correspond to important parts of Scarborough’s Reading Rope (below) and are important building blocks of reading comprehension.

The basic foundation

I’m starting each unit with a small set of words that I use to introduce the theme of that unit. These words will reappear in speaking, reading, writing and listening exercises that students will do throughout the unit. I’m choosing Tier 2 words as my foundation. Tier 2 words are complex enough that they can act as organizers for many high-frequency or sight words, but not so complex that they are domain-specific and have limited use or application. They can add significantly to a language-user’s ability to communicate because of their flexibility and application in multiple areas.

For my high-school students, being able to use words like these is a confidence booster because they don’t feel super simple or babyish. They are words that are likely to show up in written texts, and will help support comprehension, and will better support their writing which often originates in English in their thinking and then is expressed in French.

Practicing with the basic foundation

Once my students have figured out which words are represented on their list, we practice using them in a range of modalities. We say them out loud, we say them with the definition, we write sentences with them, and so on. If they have different forms, we practice with those as well. These might include things like verb conjugations or singular, plural, masculine and feminine forms of a word. Some words have more than one meaning, depending on the context in which they are used. Learning these aspects of words takes practice, repetition, and multiple exposures.

Expanding the foundation

After practicing with those basic building blocks of the foundation, it’s time to expand the foundation. To do this, I build out from the original list by adding synonyms and antonyms. The synonyms and antonyms must also be tier two words, and I choose them carefully to fit the same context as the original words in the unit we are working on.

In my original list for the unit I’m using in French 10 (10th grade French), one of my words was “informer“. This is a regular verb with an -er ending, and easy to use without having to memorize exceptions or irregularities. The only aspect students need to be aware of is that the word begins with a vowel, and so some words that go in front of it (the subject pronoun “je“, or the negative “ne“, for example) will drop the “e” and replace it with an apostrophe to better fit French rules for syllable division.

I don’t think it’s necessary to always have tightly constrained rules around word selection. However, beginning with words like these makes it more likely that my students will use them with less hesitation because there are fewer rules to remember. The earlier I can encourage experimenting with words, the earlier they will build confidence in their ability to express ideas with them. The complexity will grow as we go through the course.

I gave two possible meanings for this word in my basic vocabulary list, both of which depend on context. More meanings are listed in dictionary definitions, but they’re not likely to occur or be useful in the current unit, which centers around identity. Because I knew the basic list was just a starting point and I would be adding to it, I also wanted to keep it feeling doable and limit possibilities for overload. The definitions I used show that this word can mean both “to give information” and “to ask for information”. In my synonym practice, I used the expression “demander des informations” (to ask for information), taken exactly word for word from the definition I included in the basic list. I added the verb “aviser” (to inform, to notify) as a synonym.

Considerations around word substitution

All of the words (basic vocabulary, definitions, and synonyms) are regular -er verbs. Students can work with them in the same ways, which makes word substitution an easier task in writing and speaking. This is the first unit of the course, and so I wanted to model and scaffold word substitution for my students. It’s a curricular skill that they need to be able to demonstrate, but it’s not one that students tend to pick up instinctively and it needs to be introduced in a scaffolded way before jumping to more complex possibilities.

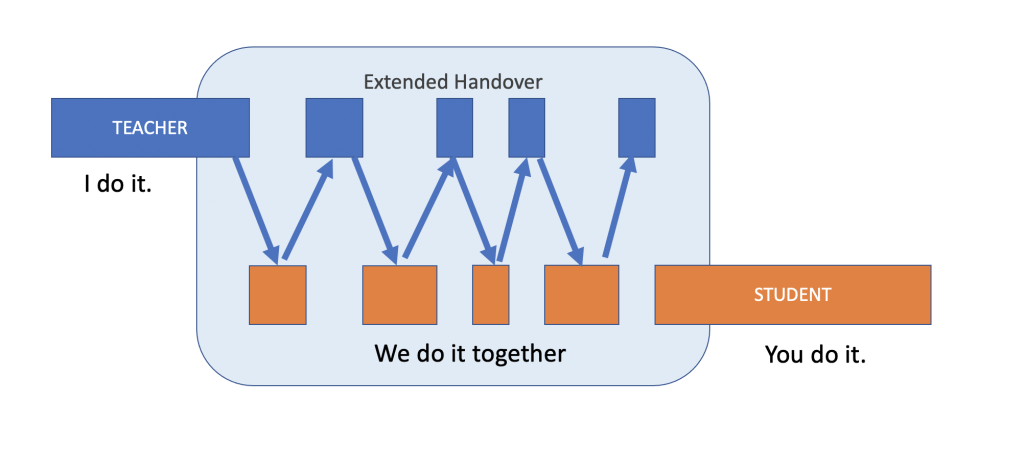

For those who may be unfamiliar with scaffolding, this is a great explanation, and includes many helpful suggestions for unit and lesson planning, instructional strategies, monitoring learning, and learning activities. Focusing on the process rather than the content or the outcome will help support student learning more effectively. It’s also worth mentioning that students are often not ready for the handover to independent practice as quickly as we think they may be. This article from TeacherHead uses math examples to illustrate this point, and the videos are well worth a listen. This diagram (taken from the article) is an important reminder that students really benefit from the supportive partnership that exists while they are learning a skill.

Why synonyms and antonyms?

In a more traditional approach to teaching unit vocabulary, my basic list would act more as an organizer or a set of subtitles. Words that would be added would be high-frequency or more specific words that would fit under each as a heading. I chose not to go that route and to get students to explore reading vocabulary in that way on a text-by-text basis. As they read, they can use the basic vocabulary as subheadings and can make their own connections with the new words they encounter, adding them to notes they create and seeing the interrelationships of words. If they find places where they think a word belongs in more than one category (which often happens), they have the agency to put it in those groups. Sorting words as they read helps to organize and structure the information for students, and makes it more likely they will remember the words and add to their content knowledge. Adding synonyms and antonyms also prepares students for what they will encounter in listening and reading, because word substitution is a commonly used practice designed to avoid repetition, add nuance or clarify context, and hold an audience’s attention. Synonyms help to provide support for alternative meanings of a word, and antonyms act as a non-example which can be helpful in clarifying what an idea is NOT.

Connecting vocabulary to skills

As I mentioned in my introduction to this blog post, language teaching and learning do center around learning and practicing skills and strategies. The content knowledge that this type of vocabulary instruction builds helps to support students in practicing skills like identification, explanation, expressing preferences, and comparing similarities and differences. These are skills that students need to know, understand and do, but not necessarily ones that would make up an entire conversation or piece of writing. Their intermittent use can make them harder to target and assess, but revisiting them in each unit of instruction as new content is introduced provides repeated opportunities for practice, feedback, and growth over time.

References

Paris, S. (2005). Reinterpreting the development of reading skills. Reading Research Quarterly, 40 (2), 184-202.

Featured image credit: Photo by Jocke Wulcan on Unsplash